Jimmy Carter Marked the Conclusion of an Era in Presidential Politics

Jimmy Carter might have been inclined to think that his election as president, nearly fifty years before his recent passing on Sunday, marked a pivotal chapter in American history akin to the moments typically heralded for new Democratic presidents.

There was some validity to this perception: He transitioned from the lesser-known sphere of Georgia politics to defeat a notable slate of national contenders, becoming the first Southerner elected to the presidency since the Civil War (with Woodrow Wilson, a Virginian, serving as governor of New Jersey).

However, Carter ultimately emerged as a transitional leader, his inconsistent foreign policy and modest domestic initiatives more closely resembling a lengthy twilight than a vibrant dawn.

He may have sensed this decline as well—just two years post-Watergate and Richard Nixon’s resignation—when he narrowly triumphed over Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford.

By the 1970s, the legacies of the New Deal and the Great Society had finally begun to wane, while the Vietnam War had disrupted the domestic Cold War consensus.

Even the longstanding Democratic grip on Congress was shaken, as the party lost both the Senate and the presidency following Carter’s single term.

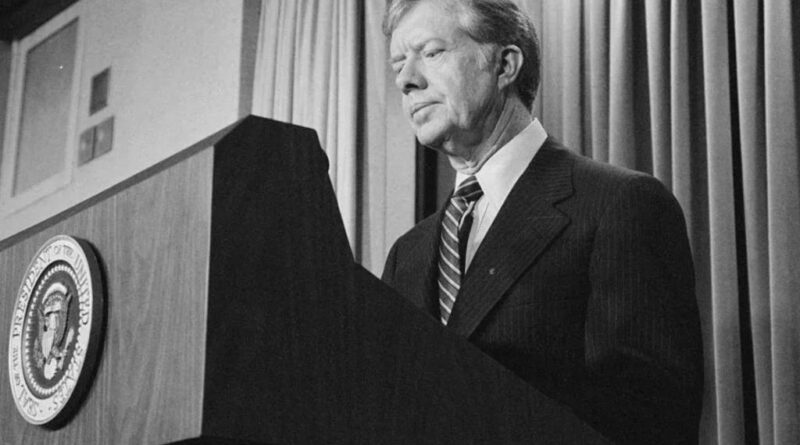

Consider the images of Carter from the start and conclusion of his presidency: In 1976, at 52, his tousled hair, bold ties, distinctive suits, and confident smile projected an eager, ambitious, and even ruthless leadership persona.

Fast forward four years later, and his hair is neatly styled and parted, the suits are dark and somber, and his once-happy smile has been replaced by a serious demeanor filled with uncertainty.

This portrayal of the Carter presidency remains ingrained in the public consciousness.

Am I overstating this? The convergence of crises that plagued his final months in office—soaring inflation, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, oil shortages and lengthy queues at gas stations, challenges from within his own party, and, most notably, the Iran hostage crisis—were not solely attributable to Carter or mere bad luck.

However, having been elected under the premise that a principled outsider was preferable to the self-serving political elite, Carter’s outsider status soon became perceived as amateurishness, indecisiveness, and weakness—most significantly, a lack of management and leadership skills.

Admittedly, Carter’s presidency did see notable yet often ironic achievements—such as the Camp David Accords, airline deregulation, and a pioneering focus on human rights in U.S. foreign policy—but when a candidate’s memoir is titled “Why Not the Best?,” it sets high expectations.

In this regard, Carter’s unconventional presidency was hindered from the outset, not merely by the hubris of inexperience, although that was present, but by his tendency to confuse high principle with actual power.

Regarding the ongoing energy crises, Carter asserted that practical solutions required not just negotiation with Congress but “the moral equivalent of war.”

He claimed that our international involvements were unnecessarily escalated by “an inordinate fear of communism.”

Carter seemed genuinely taken aback to discover that effective governance requires a degree of cynicism and negotiation skills, and ultimately, that the Cold War viewpoint on the Soviet Union was warranted.

At times obstinate, at others indecisive, Carter exasperated allies, enraged adversaries, and wasted the momentum of his groundbreaking candidacy.

His well-known tendency to micromanage the White House was both commendable and counterproductive.

Nonetheless, he left an indelible impact on the presidency—or more accurately, on presidential politics.

Upon reaching the impressive age of 100, both supporters and critics were unified in recognizing his unmistakable personal integrity, often illustrating this point with decades’ worth of images of him volunteering with Habitat for Humanity.

However, it’s worth noting that “decency” can be subjective: Carter was the first president to deliberately showcase his religious beliefs as a key element in his campaign strategy.

Previously, religion either posed a minor obstacle (Taft’s Unitarianism, Kennedy’s Catholicism) or was merely a biographical oddity, such as Nixon’s Quakerism.

Carter’s faith popularized the evangelical concept of being “born again,” and journalists found themselves monitoring his Baptist Sunday School classes—while he openly discussed, in an interview with Playboy, the biblical warning against committing “adultery in my heart.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Philip Terzian, former literary editor of the Weekly Standard, is the author of “Architects of Power: Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and the American Century.”