It’s a powerful myth that has stuck. Both Churchill himself (a prolific historian), his official biographer Martin Gilbert, and many political leaders tapping into the Churchill legend, have extolled the story. It has the benefit of being true in broad brush strokes. (Its fallacies are a topic for another article.)

Though born into the aristocratic Marlborough family, the maverick Churchill was in many ways an outsider to conventional politics. It’s hard to believe in hindsight, but he was

bitterly reviled by the British establishment before he became the heroic orator and leader of 1940 to 1945.

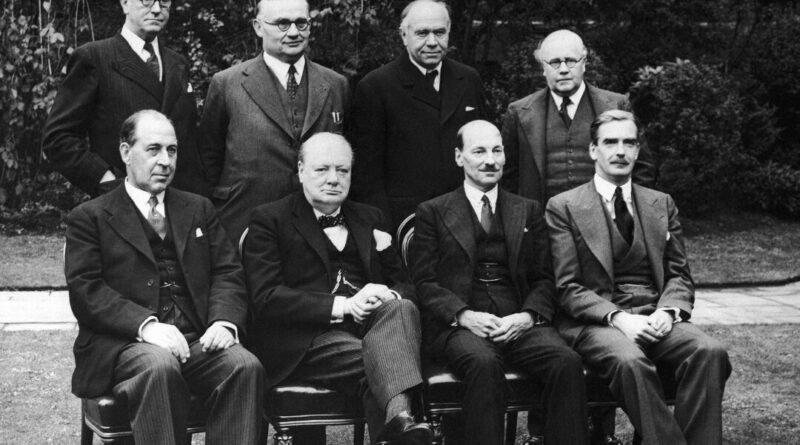

Churchill’s inner circle remained loyal to him in the wilderness years (1929–1939) when he was an MP but held no cabinet post. At that time, even Aitken declared Churchill a “busted flush.”

Still, as early as 1930, Churchill was one of the few who recognized the threat posed by Adolf Hitler, a rising rabble-rouser, anti-Semite, and leader of the Nazi Party, which increased its share of the German vote from 2.6 percent in 1928 to 18.3 percent in the 1930

elections.

Churchill perceived the threat of a resurgent Germany to the balance of power in Europe. As John Lukacs

recounts in his book “Churchill: Visionary, Statesman, Historian,” the balance of power—preventing the preponderance of any single continental power or “bully” from dominating Europe—had been British policy “for 400 years.”

By 1940, it was too late to prevent Hitler from dominating Europe. He already did.

With Churchill’s romantic view of history, including his own destiny in it, he appreciated Beaverbrook as a buccaneer rather like himself. Both were mischievous pirate-patriots in the mould of Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake, adventurers in Churchill’s dramatic bestselling epic “History of the English-Speaking Peoples.”

Churchill had confidence in Aitken’s success—his brash “ability and ruthless will,” as

biographer A.J.P. Taylor put it—and so he made him his Minister of Aircraft Production from May 1940 until April 1941.

There has been much debate around whether Aitken was really the wizard of aircraft production that the Churchill myth (and the Beaverbrook myth) claimed. Aitken’s “personal force and genius,” Churchill wrote, “swept aside many obstacles,” firing and sidelining bureaucrats to get his way.

Taylor counted Aitken “among the immortal few who won the Battle of Britain,” who, “at the moment of unparalleled danger … made survival and victory possible.” Sir Hugh Dowding, in charge of Fighter Command, praised the Beaverbrook effect as “magical.”

Churchill described Beaverbrook as his “tonic,” someone who kept him buoyant, a “real help and spur.” “Some people take drugs,” he said, “I take Max.” Together they understood the mission of the world empire of liberty led by Britain, “her message and her glory.” He called Beaverbrook his “foul weather friend” and the Battle of Britain his own “hour” of triumph.

It was a first step on the road to victory over Nazism five years later.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.