Intel CEO Retires After Company’s Multibillion-Dollar Losses

In 2024, Intel may record its first annual loss since the 1980s.

Intel Corp. announced its now former CEO Pat Gelsinger, who spent most of his more than 40-year career with the Santa Clara, California-based semiconductor manufacturer, had retired on Dec. 1.

Gelsinger, who took over as Intel’s chief executive in February 2021, pushed it to begin making chips for other semiconductor companies while simultaneously designing and manufacturing its own chips. His plan cost billions and has yet to deliver results.

The change initially sent Intel’s stock price up as high as $25.44 a share, but as of Tuesday afternoon, it had sagged back to about $22.50 a share. Since the beginning of August, it has hovered around the $20 per share mark. Since the beginning of 2024, its value has fallen by about 55 percent.

In addition, Intel’s stock is currently trading for less than half of the $58.18 it closed at on Jan. 31, 2021. Following its nearly three-year bear run, Intel received a significant downgrade in November when it was replaced on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) by rival chipmaker Nvidia Corp. At the time, Intel had the lowest stock price of any of the companies in the DJIA.

That followed a trend of steadily worsening financial results under Gelsinger’s stewardship, according to Intel’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). At the end of 2023, according to its annual filing for the same year, Intel’s net income, or profit, came in at $1.675 billion, a drop from about $8 billion in 2022, about $19.9 billion in 2021, and about $20.9 billion in 2020.

When Intel last published an earnings report with the SEC on Nov. 11, it reported a net loss of about $19.1 billion through the first nine months of 2024.

Difficult Decisions Ahead

In a Dec. 3 research note shared with The Epoch Times by Bank of America Global Research, a team of analysts led by Vivek Arya, a research analyst at Bank of America Securities, said Gelsinger’s departure was unexpected but not a “complete surprise.”

In the note, Arya and his co-authors said the move raises questions about whether Intel will begin to divide its products and foundry businesses, “which would grant both businesses their much-needed operational and financial independence.”

“There could be more flexibility for the potential split between various [Intel] entities. … We still highlight both businesses are undergoing their own strategic, structural, financial, and competitive issues, with no near-term solution in sight,” the Tuesday research note said.

The same note wondered if Intel would maintain the so-called IDM 2.0 strategy Gelsinger had pursued as Intel’s leader. The strategy pushed Intel to maintain its status as a so-called integrated device manufacturer (IDM)—a company that designs and makes its own chips—while also launching a new foundry business that can compete with other semiconductor makers like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and Samsung Electronics Co. A foundry is a semiconductor business that can make chips for companies that design them but cannot make their own.

Furthermore, the note said jumping out of the foundry business will be challenging for Intel, given its current investments and the rewards it is receiving from the U.S. government as part of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. On Nov. 26, Intel announced the U.S. Department of Commerce awarded $7.86 billion “in direct funding” through the CHIPS Act to “advance Intel’s commercial semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging projects in Arizona, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon.”

The Bank of America note said the CHIPS Act requires Intel to maintain ownership of a significant portion of Intel’s foundry if it wants to keep the money. In effect, the award “prevents it from fully separating the foundry business,” the report said.

Finally, Intel needs more demand for its products. Intel’s semiconductors remain geared toward personal computing. The brand was famous for its Intel Inside stickers in the 1990s, when PCs started appearing in many American homes; but it is losing ground to its competitors Advanced Micro Devices Inc. (AMD) and Arm Ltd. in both the PC and server spaces.

“PC demand outlook remains grim,” the Bank of America research note said. “[Intel] remains 50–55 percent exposed to PCs and has no competitive AI accelerator products.”

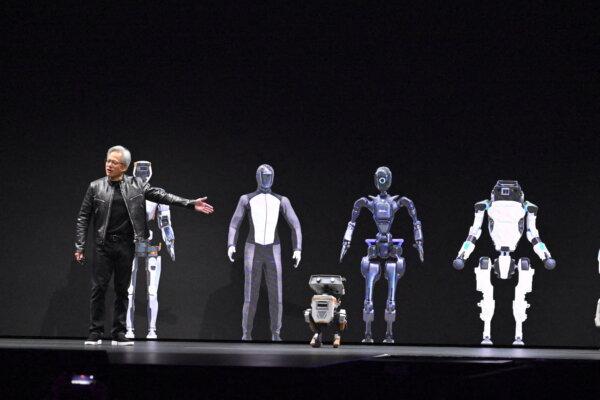

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang speaks during the annual Nvidia GTC Artificial Intelligence Conference at SAP Center in San Jose, Calif., on March 18, 2024. Josh Edelson / AFP

A Flawed Comeback Plan

According to Reuters’s investigation of Gelsinger’s tenure published in October, the ex-CEO had an excellent pedigree to lead the company, but made numerous mistakes.

Gelsinger, who started at Intel in 1979 as a teenager and rose to become its chief technology officer before moving to another company, reportedly returned to Intel that misread the future of the technology industry.

According to Reuters, before Gelsinger’s tenure, Intel chose to remain focused on making chips for desktop computers and servers. Plus, Intel declined to make chips for Apple Inc.’s iPhone and on a chance to be an early investor in what is now a leader in generative AI OpenAI.

Upon Gelsinger’s return, Intel began to pursue a strategy of becoming a foundry company and an IDM. This would allow it to compete with worldwide foundry leader TSMC. In March 2021, he announced the company would spend $20 billion to build two factories in Arizona and devote significant resources to developing new chip-manufacturing processes.

In January 2022, Gelsinger and Intel doubled down on the plan by announcing another $20 billion plan to build two factories in Ohio. That same year, as demand for its products began to drop, the company announced it would lay off employees while continuing to pour money into chip factories.

Also, in 2022, graphics processing unit (GPU) leader Nvidia began a meteoric rise as OpenAI launched the revolutionary AI chatbot ChatGPT. Seeing the apparent change in market demand from Intel’s central processing units (CPUs), Gelsinger began to promote a new chip called Gaudi—designed by Intel but made by TMSC—that could serve as a substitute for Nvidia’s GPUs.

Nvidia’s GPUs were first made for video gamers and digital artists, but they have become essential cogs in the generative AI world and are often in short supply.

So far, Intel has yet to develop a successful GPU product of its own.

Intel’s so-called 18A process—a plan championed by Gelsinger to make chips for other firms in its foundry business—has not yet delivered results, either, and the preliminary results are not encouraging for potential customers.

As of September, Intel had said it would be able to launch its 18A process in 2025. However, Reuters said it spoke with sources who think 18A won’t be able to make chips at a high volume until 2026.

Reuters contributed to this report.