Trump Wants to Eliminate the Debt Ceiling—What Is It and How Did We Get Here?

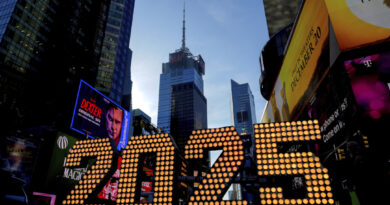

The U.S. government rang in the new year by reinstating the debt ceiling on Jan. 1, preparing the nation for another showdown in 2025 between Democrats, fiscal conservatives, and President-elect Donald Trump.

As Congress narrowly avoided a government shutdown just before Christmas, Trump renewed the debt ceiling debate by advocating for its abolition or multi-year extension.

“The Democrats have said they want to get rid of it,” he said. “If they want to get rid of it, I would lead the charge.”

A day later, the president-elect proposed extending the debt limit to 2029.

Because the lower chamber neither removed nor extended the debt ceiling during last month’s continuing resolution battle, Congress will engage in a contentious and divisive quarrel in the coming weeks or months.

What is the debt ceiling? Where does it stand? And what have previous conflicts over the debt ceiling looked like?

What Is the Debt Limit?

The debt limit sets the maximum amount of outstanding debt the United States can incur to pay its obligations, such as Medicare, social security, and interest on the national debt.

The purpose of the debt limit is to regulate spending and ensure that lawmakers remain fiscally responsible.

The U.S. government spends more than it takes in, accumulating sizable budget deficits that add to the growing national debt.

A Trip to 1917

Before 1917, Congress permitted the government to borrow for a specified period. After repayment, the government could not borrow again without Congress’s approval.

Congress established the debt ceiling through the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917, as part of the federal government’s effort to finance the First World War with Liberty Bonds.

The legislation helped then-President Woodrow Wilson speed up funding to fight the war, though lawmakers restrained borrowing to approximately $12 billion and required legislative efforts to increase the limit.

Additionally, the newest measure authorized a continual rollover of debt without congressional approval.

President Woodrow Wilson gives a speech to Congress at the U.S. Capitiol on Dec. 4, 1917. FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Political Football

Over the last 30 years, the debt limit has become a political football, with both parties using it as leverage.

In this game, one party will accuse the other of holding the country “hostage.” The other side will state that the fight is necessary to improve the government’s finances and long-term fiscal health.

Scores of well-known Democrats, including then-senators Barack Obama and John Kerry, argued against raising the debt ceiling under President George W. Bush.

“The fact that we are here today to debate raising America’s debt limit is a sign of leadership failure. It is a sign that the U.S. government can’t pay its own bills. It is a sign that we now depend on ongoing financial assistance from foreign countries to finance our Government’s reckless fiscal policies,” Obama said in March 2006.

In April 2011, when the country embarked upon another debt ceiling debate, White House Press Secretary Jay Carney stated that President Barack Obama had “regrets” for his vote in 2006 against raising the debt ceiling.

Republicans spearheaded debt limit standoffs during the Obama administration. However, Kerry changed his mind and espoused how crucial it was to raise the debt ceiling.

“[Republicans] are insisting, not as a matter of common sense or as a matter of logical economic policy, but insisting as a matter of politics and ideology on holding the entire economy of our country hostage and be damned with the risks,” Kerry said on the Senate floor in July 2011.

President Barack Obama leaves after speaking on the status of debt ceiling negotiations in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House on July 29, 2011. Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

Trump participated in two debt ceiling fights during his first term in the White House.

The first took place in 2017. He quickly cut a deal with Democrats to boost defense and non-defense spending by $300 billion, in exchange for extending the debt ceiling for more than a year.

In 2019, Democrat leaders touted conditions before agreeing to increase the federal government’s borrowing cap again.

Then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) demanded higher spending limits for the Pentagon and domestic agencies.

“When we lift the caps, then we can talk about lifting the debt ceiling—that would have to come second or simultaneous, but not before lifting the caps,” Pelosi told reporters in June 2019.

Despite his latest remarks, Trump has previously extolled the debt limit, describing it in 2019 as “a sacred element of our country” that should not be used as a bargaining chip.

“We can never play with it,” he said to reporters.

However, Trump flirted with eliminating the fiscal fixture in the early stages of his presidency.

“For many years, people have been talking about getting rid of the debt ceiling altogether, and there are a lot of good reasons to do that,” he told reporters. “It complicates things, it’s really not necessary.”

President-elect Donald Trump speaks during a meeting with the House GOP conference in Washington on Nov. 13, 2024. Allison Robbert/Pool Photo via AP, File

A Biden-McCarthy Special

In June 2023, President Joe Biden and then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) agreed to raise the debt ceiling and suspended the measure until Jan. 1, 2025, through the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

The national debt was about $31.4 trillion at the time. Today, it is above $36.1 trillion.

On Dec. 29, Trump took to Truth Social to call the extension of the debt ceiling “one of the dumbest political decisions made in years.”

“There was no reason to do it—nothing was gained, and we got nothing for it—A major reason why that Speakership was lost,“ he said. ”It was Biden’s problem, not ours. Now it becomes ours.”

The national debt clock is displayed at a bus station in Washington on Jan. 2, 2025. Madalina Vasiliu/The Epoch Times

What Wall Street Says

The fiscal brinkmanship has been a source of anxiety for Wall Street.

The world’s largest economy has never defaulted on its debt. However, lawmakers have regularly waited until the last minute to raise or suspend the debt ceiling, which has experts ringing alarm bells.

All three major credit rating agencies have penalized the U.S. by either downgrading America’s credit rating or lowering outlooks.

The first occurred in August 2011, when Standard & Poor’s trimmed the credit rating for U.S. government long-term debt from the high of AAA to AA+.

In 2023, Washington was slapped over the previous round of debt ceiling negotiations. Fitch Ratings slashed the U.S. long-term credit rating from AAA to AA+, and Moody’s Investors Service cut its outlook on the U.S. credit rating from “stable” to “negative.”

“The repeated debt-limit political standoffs and last-minute resolutions have eroded confidence in fiscal management,” Fitch analysts said in August 2023. “In addition, the government lacks a medium-term fiscal framework, unlike most peers, and has a complex budgeting process.”

Experts have warned that a default would trigger an economic catastrophe and lead to global repercussions.

The primary concern is that a default would shatter confidence in U.S. government debt, causing higher interest rates to attract investors. This, in turn, would raise borrowing costs for the government, businesses, and consumers.

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson (C) speaks with reporters at the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 20, 2024. The House voted on Dec. 20 to avert a government shutdown with just hours to spare, with Democrats joining Republicans to advance a funding bill keeping the lights on through mid-March. The Senate, then, passed the bill. Richard Pierrin/AFP via Getty Images

Economists at the Brookings Institution estimate that a default could increase interest payments by $750 billion over the next ten years.

“Risking a default on the national debt is a costly and counterproductive way to try to tame the debt. It could thrust the world economy into a recession or depression,” wrote Leonard Burman, an institute fellow at the Tax Policy Center.

“And that outcome is far from the worst possibility.”

Desperate Times Call for ‘Extraordinary Measures’

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) may have a solution to the debt ceiling standoff.

Johnson outlined a debt ceiling agreement that could be reached through the reconciliation process. This agreement would combine a $1.5 trillion debt ceiling increase with $2.5 trillion in cuts to net mandatory spending.

In a Dec. 27 letter to congressional leaders, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen noted that the U.S. government will hit its debt limit as early as Jan. 14 unless legislative action is taken.

When Washington hits the debt ceiling, Yellen says, the Treasury Department will employ “extraordinary measures.”

These are temporary financial maneuvers to prevent a default on obligations. They usually involve suspending debt issuance, redeeming existing securities earlier than scheduled, and halting new investments in government funds.

In addition, officials can tap into the government’s existing balance in its checking account at the Federal Reserve.

As of Dec. 30, the Treasury General Account has more than $700 billion at its disposal.

Should the Treasury exhaust all these options, the U.S. government would default. Yellen hopes it will not lead to this situation.

“I respectfully urge Congress to act to protect the full faith and credit of the United States,” Yellen said.

That said, what exactly will happen is unknown, because the United States has never before defaulted on its debt over failure to raise the debt ceiling.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen listens at a hearing with the House Committee on Ways and Means in the Longworth House Office Building in Washington on April 30, 2024. Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

When Is the X-Date?

The X-Date references the date when the U.S. Treasury is anticipated to exhaust its extraordinary measures to avoid a default.

Economists at the Economic Policy Innovation Center project that June will be vital for determining the X-date.

Various factors will influence the X-date over the next six months. Quarterly tax payments are due in mid-June, and a one-time-use extraordinary measure will be available on June 30.

Monthly deficits will also prove integral. April usually presents Congress with enormous surpluses as individuals pay their income taxes and corporations pay quarterly taxes. May and June, on the other hand, usually post large deficits as government expenditures outpace revenues amid immense Medicare and Social Security benefit payments.