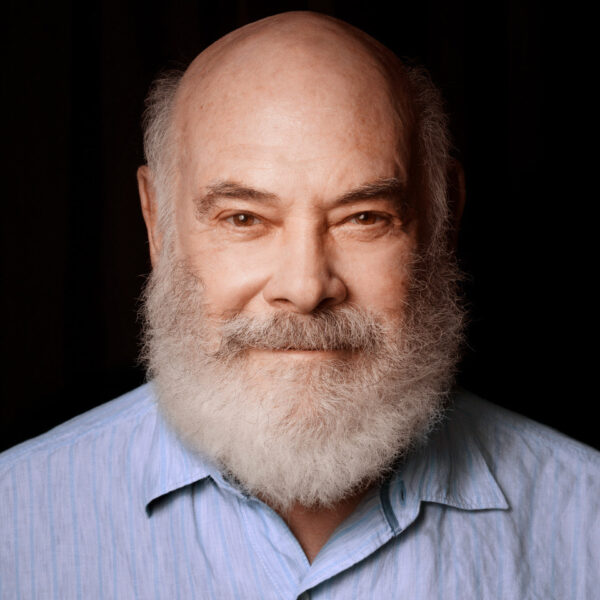

A Conversation with Dr. Andrew Weil

Hello, my name is Conan Milner and this is Words of Wellness, a show where we talk about health from mind, to body to spirit.

So what does it mean to be healthy? Is it merely the absence of disease? Or is there something more to it?

Not long ago, any serious discussion of health looked exclusively to the domain of modern medicine for answers. Today, however, we’re much more willing to expand our view to look beyond the bounds of pharmaceuticals and CT scans, and entertain health ideas like acupuncture or Ayuredic remedies.

This broader perspective of health has now become part of our modern culture, and more and more doctors are embracing it. It is found in categories we now call integrative alternative or complementary medicine.

My guest today has been an influential voice in forging this more inclusive point of view. When it comes to how we think about health, his many books and articles have expanded our notion of what it means to be healthy, and he has also lent loads of credibility to healing modalities that lie outside the conventional model of modern medicine.

So what forces shaped this influential figure? In the 1960s, Dr. Andrew Weil earned two degrees from Harvard University, one in medicine and another in botany. Throughout the 1970s and 80s. Dr. Weil was on the research staff of the Harvard botanical Museum, conducting investigations into the medicinal and psychoactive properties of plants.

Over the last few decades, Weil has helped many health care consumers see things like deep breathing, meditation and herbs as viable and effective forms of healing. Today, Dr. Weil is the director of the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona, where he’s also a clinical professor of medicine and professor of public health.

Dr. Weil, thanks so much for talking to me today.

I’d like to start off our discussion by talking about where your perspective that I just described comes from. How does a doctor trained at Harvard in the 1960s become interested in things like herbs and meditation?

Dr. Andrew Weil: Well, I have a long standing interest in many of these subjects. My mother got me interested in plants when I was growing up. And that interest eventually led me to study botany when I was an undergraduate, and started me off on a career interest in medicinal plants. I was also always fascinated by the mind and how the mind interacted with the body. Eventually, that led me to take a course in clinical hypnosis, which has been very valuable to me.

I became interested in what was called alternative medicine when I was an undergraduate, and began reading about things like chiropractic and naturopathic medicine, which I knew nothing about. So a lot of these interests were there before I went to medical school. And when I went to medical school, I was very disappointed to find that there was very little awareness of these subjects as well as other things that I thought were very important, such as nutrition. So I decided I had to study that on my own to round off my education.

Conan Milner: You say there was little awareness of these subjects, but from what I understand, there was not just a lack of awareness, but also derision of the subjects. When I first came to know your work in the 1990s, at that time, alternative and complementary medicine, these kinds of things, were just starting to break into the mainstream consciousness. Why do you think there was so much resistance before this to these ideas? What do you think it took to get people to open up?

Dr. Weil: Medicine has a very guild-like atmosphere. It’s a very closed system. It doesn’t pay attention to ideas that come from unfamiliar sources.

When I was starting to study medicine, acupuncture was put in the same category as sticking pins into voodoo dolls. And it wasn’t until there began to be general interest from the public in it that doctors began to look at it.

Botanicals were often [seen as out of] left field. I was very disappointed that the people who taught me pharmacology seemed to know nothing about the plant sources of the drugs that they were teaching. And the whole area of mind-body medicine was completely ignored because the materialistic paradigm that dominates Western science and medicine doesn’t look at the mind as real and certainly not being capable of having real influences on the physical body. So I think there’s a lot of reasons for that, but all of it has greatly limited the effectiveness of conventional medicine.

Milner: This materialistic paradigm you talk about is kind of the hallmark of science and the scientific method that we’ve come to understand. But, you know, we’re starting to break the bounds of it and look into how traditional cultures looked at these things.

So what else goes into your thinking? How did you come to see the validity of the subjects that lie outside of modern medicine,

Dr.Weil: Well, a lot of it is my own experience. Because, you know, I have had many experiences in my own body of healing that have been stimulated by methods that I learned nothing about in medical school. After I left clinical medicine, I traveled around the world for a number of years, and looked at healing practices and other cultures. I worked with a variety of non-conventional healers. And I saw some things that made no sense to me. I saw others that were interesting, some that seem very valuable. And gradually, I put together my own system of practice, which I first called natural preventive medicine, which I then came to call integrative medicine.

Milner: One of the characteristics that I notice between conventional modern medicine and a more holistic approach is that the latter typically demands more responsibility from the patient. Instead of looking to the doctor or pill to fix their problems, patients are expected to do most of the heavy lifting themselves. This usually means dietary improvements, exercising or some other meaningful lifestyle change. I wonder if you can talk about the obstacles you see most often in patients hoping to improve their health, but who flounder at making the changes they need.

Dr. Weil: Lifestyle medicine is a foundational plank of integrative medicine, and a major curricular area that I and my colleagues teach at the University of Arizona. You know, when we study drugs, we test them against placebos, we don’t test them against lifestyle change, which would be much more useful data to have. The practical problem of lifestyle change is that it requires work and it takes time. Patients want to be medicated, and the only treatment methods that doctors learn is to use pharmaceuticals.

So it’s on both sides. I think most physicians wouldn’t know what to do if you told them that they couldn’t use drugs in treating patients and most patients who didn’t get a prescription at the end of a medical interaction would feel cheated and go to another doctor until they got one. So that is a mindset problem.

The other reason, as I said, is that drugs often work quickly, and don’t require work, whereas lifestyle change may take weeks or more to show results, and they require effort. So those are big obstacles that you have to overcome.

I have many physician colleagues who ask me how they can do that. And I have two suggestions. One is that the doctor should model health for patients. You can’t tell a patient to exercise if you yourself don’t have good habits of physical activity, for example. One very good technique is motivational interviewing, in which you dialogue with a person or with a patient to find out the mental patterns that may be in the way of making changes, and then finding ways to overcome them.

Milner: A couple of podcasts ago I just happened to talk to a therapist who works with addiction patients. He introduced me to this concept of motivational interviewing, I had no idea that just talking to someone like this could have this kind of impact.

Dr. Weil: It’s a very useful technique. It’s learnable. It’s something that we teach in our fellowship training at our center. So that’s a good thing to read up on.

Milner: As you were describing the conventional model of the doctor-patient relationship where the patient looking to the doctor to do all the work. It struck me as how enabling this model is and how so much of our society is all about quick fix.

Dr. Weil: There’s also larger problems there that have to do with powerful vested interests that oppose this kind of work. For example, if you look at nutrition, we’ve made the unhealthiest foods the cheapest and most available. So it’s how people eat. Some of that has been done through federal government subsidies of commodity crops that make products like high fructose corn syrup, and refined soybean oil very cheap. That’s why these manufactured food products are so ubiquitous. And that’s just one example of how, as a society, we have not supported healthy lifestyle choices.

Milner: Yeah. I can see how all these factors conspire toward the poor health outcomes we see in the modern age.

Dr. Weil: Well, we have devolved quite a bit. You know, we have epidemics of lifestyle related diseases, type two diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, the obesity epidemic and young people is cause for very great concern. It’s being followed quickly by type two diabetes and cardiovascular disease in young people.

We have an aging population, and old people get sick and become major drains on the healthcare system. We spend in the U.S. more per capita on health than any other developed country. And we have worse health outcomes than any other developed country. So I think we are not in good shape at all, and it’s getting worse. And we have to make some big changes.

A big problem is that what we call our healthcare system is really a disease management system. And the diseases we’re trying to manage are not well managed by conventional medicine, because they’re rooted in poor lifestyle choices. And the kind of medicine that conventional medicine relies on is too expensive because of its dependence on expensive technology. And that’s sinking us economically. And also, we have these terrible health outcomes. So something has to change.

Milner: Let’s talk a little bit about what you’re doing to facilitate that change. I know you spent much of your career training other doctors in a more holistic approach to medicine, in essentially training patients toward a better lifestyle. What do you think makes doctors gravitate toward this philosophy of practice that you advocate for? What’s in it for them? How do they come to see this avenue as a more enlightened way to practice?

Dr. Weil: For many doctors, the practice of medicine has become very unsatisfying. When I went to medical school, medicine looked like a very desirable profession. It offered the promise of autonomy. There was great respect for it in the general public. You could be your own boss, but hat’s all disappeared in the era of for profit medicine. Many physicians say they wish they’d gone into another career. They find being told how many minutes they have to see a patient very unsatisfying. I mean, there are a lot of reasons for physician unhappiness.

There has been a steady demand from consumers that’s been going on since the 1970s for more natural treatments and use of what had been called alternative therapies. But now I think it’s really economic necessity that’s driving a lot of this. Plus the unhappiness of physicians.

Our Center at the University of Arizona is the leading educational effort in the world to train health professionals. We train physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and physicians assistant students. Our main educational offering is an intensive two year fellowship. It’s 1000 hours taught online to remedy all of the deficiencies in medical education such as nutrition, botanical medicine, the strengths and weaknesses of alternative medicine, and the importance of mind body interactions. I think now we’ve graduated 3000 physicians and allied health professionals from these training sessions.

In addition, we have a condensed curriculum that’s being put into residency training. We have 100 residency programs in the U.S. that have adopted it, as well as some in Canada and in other countries. We also train medical students, and we have offerings for the general public. The demand for this kind of training and information has steadily grown.

Let me give you the website of our center because everything’s there for the general public as well. https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/

You can see the full range of our activities there. You know, our center has grown enormously in the 20 some years that it’s been in existence. And integrative medicine is really becoming mainstream. There are textbooks in it. I think two thirds of the nation’s medical schools have joined a consortium for integrative medicine. So you know, it is happening.

Milner: But one of the obstacles, I guess you could say, as I’ve been talking to doctors about practicing medicine today is insurance. Specifically, what insurance will and won’t cover. This can potentially cripple alternative practitioners who don’t have their practice covered, or aspects of it, and their patients are forced to pay out of pocket.

Talk a little bit about this, because insurance is how we consume health care, particularly in this country. This has a big influence on the kind of treatments that patients choose.

Dr. Weil: Definitely, this is a major roadblock. And, frankly, I think our priorities of reimbursement are completely backward. We happily pay for interventions for drugs, but we don’t pay for a doctor to sit with a patient, and counsel them about better ways of eating, or teach them a breathing exercise. And that has to change.

When we graduate these people from our intensive training, I feel bad because we then turn them out into a world where everything is stacked against them. But many of our graduates have found creative ways to get around some of this. One is by having group visits. Another is by working with billing codes to get reimbursed for the services they provide.

This is also slowly changing. But this is one example of how powerful the vested interests are that control the system at the moment. You know, as dysfunctional as our healthcare system I (and it’s very dysfunctional) it’s generating rivers of money that are flowing into very few pockets. It’s the pockets of the insurers, the big pharmaceutical companies, the manufacturers of medical devices, the for profit, healthcare systems. Those vested interests don’t want anything to change, and they have total control of our elected representatives. So I don’t see any possibility of change coming from the government.

The only way this is going to change is if there is a grassroots social/political movement. If enough people get angry enough about how things are then we will begin to elect different kinds of representatives that are not beholden to those vested interests.

So it’s a big problem. But I think time is on our side. The economic necessity is going to drive this because we now spend, something like 18 percent of our gross domestic product on health care. It’s predicted to go up to 20 percent. And it’s completely unsustainable, especially since we have such poor health outcomes.

The great promise of integrative medicine is that it can lower healthcare costs and preserve or I think enhance outcomes by, first of all, shifting the whole focus toward prevention and health promotion. And second, by bringing into the mainstream treatments that are not dependent on expensive technology.

Milner: That is a great vision. I read that the pharmaceutical industry is the top lobbying group in Washington. It spends far more than Big Oil.

One of the things you mentioned is that the integrative model requires more time. I’ve read that the average doctor visit is about 11 minutes. Most of the time the doctor spends in front of the computer typing.

But in order to really practice medicine in an integrative way, a significant amount of time has to be spent with the patient. I wonder if you can talk a little bit about that. I think that this is a point that people need to understand. This is about more than just a quick in and out, find a fix and move on.

Dr.Weil: Yeah, that’s another of the core philosophical principles of Integrative medicine: the physician patient interaction has to be protected. And part of that means allowing enough time for a therapeutic relationship to develop throughout history. In all cultures, that relationship has been seen as special, even sacred.

There’s something that happens when a medically trained person just sits with a patient, and allows them to tell their story. That alone can initiate healing before any treatment is given. That interaction has been the source of some of the greatest satisfaction in practicing medicine. And it’s all disappeared in this era, when you’re told as a physician, how many minutes you have with a patient.

And, by the way, 11 minutes is [not common]. It’s long, and it’s unlikely that if you have five or 10 minutes with a patient, that you can form the kind of therapeutic relationship that fosters healing. The disappearance of that is another reason for the great dissatisfaction of practitioners today. So that has to change.

When I see a patient, I often take an hour. I spend the first half of that taking a history, and then I give recommendations. I could probably do that in 30 minutes if I had to, but it has to be enough of a chunk of time that I can get a sense of that person and establish a therapeutic relationship with them.

To change this, we need to be able to show the people who pays for health care. That it is in their interest. That it’s going to save them money to practice integrative medicine. In order to do that, we have to collect data on outcomes and effectiveness of integrative treatment versus conventional treatment. This has to be done with large groups of people. We could pick, say, a dozen conditions, which are now absorbing the most healthcare dollars, where we think integrative medicine can really shine—things like back pain, allergies, and autoimmune diseases.

And then you want to match patients. Match them for age, medical diagnosis, and compare them. One group goes to integrative treatment. One goes to conventional treatment. You follow them, and you compare medical outcomes, cost outcomes, and patient satisfaction over time. That kind of data is what we really need today in order to show the payers that integrative medicine is in their interest. I’m quite sure we can do that. But it’s not so easy to set up those studies.

Milner: Yeah, it’s always about funding and the will to make it happen.

I want to talk a little bit about some of the positives of modern medicine, because, although you are known for advocating natural approaches, you also stress that modern medicine has its place. That there are aspects of it that are useful and life saving.

I just wonder if you have any general advice about when patients might want to look to pharmaceuticals to fix their problems, or when to choose something like herbs, vitamins, acupuncture. Is there a rule of thumb, or is this something that can only be judged on a case by case basis?

Dr. Weil: No, I think there are some general rules, and it’s very important for patients to understand when you should go to conventional medicine. When can you afford to wait and try other methods? When do you want to use the two together?

In general, modern conventional medicine has become better and better at managing trauma, critical illness, very severe illness, very fast moving illness. We have powerful techniques for treating bacterial infections, although we’re losing some of that power as bacterial resistance develops. We have effective drugs for controlling high blood pressure. We have developed techniques for dealing with some forms of cancer very effectively. Breast cancer has now become, for many people, a chronic disease that is manageable. It’s very different from when I was first studying medicine. These are all examples of where conventional medicine shines.

On the other hand, conventional medicine is not very good at dealing with the lifestyle related diseases that are now epidemic, with chronic disease in general, and with mental and emotional illness. I know there are broad categories of disease for which conventional medicine is not good. And if you rely on that you’re incurring unnecessary expense and maybe delaying the possibility of promoting healing.

Milner: It’s clear that the things that modern medicine performs worst at are the biggest problems in our healthcare system.

Dr. Weil: I often give this example. If I were in a serious car accident, I would not want to first go to a chiropractor, or a shaman or an herbalist. I want to go to a trauma center and get put back together. But then, as soon as I could, I might use other methods I know about to speed the healing process.

Milner: I wanted to come back to this issue of money again, because I was thinking about your proposed study for comparing health outcomes. Getting people to understand the cost of conventional medicine is a huge factor in getting people to understand the strengths of a more integrative approach. The problem I see is that the costs, because of insurance, are hidden from people. They’re not paying for the services out of pocket, so they do not see where the money’s going. As far as they are concerned, it’s free.

Dr. Weil: Yeah, that’s also true with prescription drugs where people’s co-pays seem very modest. They are unaware of how much somebody is paying for them.

I think Americans also have no idea that they’re paying often many times more for the same drugs as people pay in Europe. The pharmaceutical companies justify the expense by saying they have to spend so much on research. But the amount they spend on research is insignificant compared to what they spend on promotion.

I think understanding the money aspect of all this is key in terms of getting those studies done. The problem is that the NIH does not see this within its mission. So who’s going to do them? One thought I have is if we could enlist the private sector. If we could get some corporations to fund at least pilot studies, because corporations are hobbled by health care costs. They’re only interested in what works. And they’re not bound by ideology. So this is an initiative that I and people at my center are working on—to try to get at least some of these beginning studies going.

Milner: So we talked about how much the landscape of modern medicine has changed since you became a doctor, and how much it still needs to change. But I wonder if there’s any models that you see in other countries, perhaps, or other communities where it’s working, where at least they’re heading towards something that we might want to aim for too.

Dr. Weil: I haven’t seen any place that does it right, but I’ve seen elements that strike me as good in other places, for example.

It’s unconscionable that the richest country on earth can’t provide basic health care coverage to all of its citizens. As you know, a number of other countries, like Canada, have universal health care, and I think that’s something we have to work toward.

Germany has a much greater respect for and incorporation of natural treatments. And there’s a two tiered system there. There’s government insurance, and private insurance that seems to work better than what we have in America.

In many countries that have national health systems like the UK and Japan, you see the same problems developing as here: they have an aging population, epidemics of lifestyle related diseases, escalating costs, and the national healthcare system is breaking down, it can’t deliver.

So what I’ve seen as I look around the world is that as these forces develop, the openness to integrative medicine begins to appear. This is why I say time is on our side here. Things have to change in this direction.

Milner: As long as enough people realize that there’s a problem. I think that that there is now. Even the most conventionally minded people that I have talked to realize that it can’t keep going the way it is.

Dr. Weil: And an awful lot of people that I know, who have had interactions with the healthcare system in the past few years have been very unhappy with the nature of those interactions for one reason or another. So I think there’s a lot of unhappiness out there that, at some point, could be the basis for the kind of social political change that I think is necessary.

Milner: I always like to end on something positive, so I wonder if you can offer any words of wisdom to patients who are struggling in a less than perfect healthcare system, about what they can do to support their own health.

Dr. Weil: Sure. You know, I wear two hats. One is an academic hat in the university system. And that’s been focused on training health professionals. But also I have long worked to provide information to the general public on just those issues. So I would urge people to look at my books. I have a number of books that are all in print on health with a lot of information on self care. My website, www.dr.weil.com has a great deal of practical information for managing health conditions and on various treatments.

Through our university website that I gave earlier, there’s a find-a-practitioner link, where you can locate graduates of our program, in the area where you live in, in all specialties. So if you want to take advantage of that kind of information those are the resources that are out there.

Milner: Sounds good. Well, I just want to say, I appreciate the work that you’ve done to empower the average patient at a time where the healthcare system is so lacking.

Dr.Weil: I think this is the future. Things have to move in this direction.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times. Epoch Health welcomes professional discussion and friendly debate. To submit an opinion piece, please follow these guidelines and submit through our form here.