Biological Factors of Happiness, and How It Impacts Our Physical Health

Distressed Patriotic Flag Unisex T-Shirt - Celebrate Comfort and Country $11.29 USD Get it here>>

Are marshmallows the key to happiness?

They might be—but not in the way that you think.

In the classic “Marshmallow Experiment” on delayed gratification, researchers brought hundreds of children—mostly around 4 and 5 years old—into a room and offered them a deal. The researcher said that the child could eat a marshmallow now. Or, they could wait, and if they did not eat the marshmallow for 15 minutes, they would be given a second marshmallow.

It was a simple choice: eat one marshmallow now, or two marshmallows later.

The researcher’s left the room, and video footage of the children struggling to not eat the marshmallow has become famously entertaining. Some children ate the marshmallow right away. Others waited and got a second marshmallow later.

The study ended up being groundbreaking in part because, in follow-up studies, the children who were able to delay their gratification ended up doing better in most facets of life—they had had better performance at school, coped better with stress, were rated as more socially competent, and more.

But the study also sheds some light on happiness and how to achieve it.

What Is Happiness? Biological Factors

It turns out that some factors of happiness are baked into our genes.

One study suggests that genetic factors contribute about 35 percent to 50 percent of our happiness. Several genes have been identified that seem to affect how we experience emotions and our base-level mood.

These seem to have an effect on our brains. Some parts of the brain (such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and limbic system) and several neurotransmitters (including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and endorphin) play a role in how we experience happiness.

Other studies point to the role of hormones in regulating our mood. Cortisol and adrenaline (from the adrenal glands) and oxytocin (from the pituitary gland) are some of these.

Together, these biological structures help set the stage for how we feel.

But our experiences and how we act also play a role in our happiness.

Hedonic and Altruistic Happiness

The meaning of happiness is subjective. Everyone may have their own definition.

This concept of well-being is subjective and consists of three components: life satisfaction, the presence of a positive mood, and the absence of a negative mood, together often summarized as happiness.

Psychologists have actually spent decades investigating the factors that contribute to our health and happiness. And the research gets pretty interesting. Positive psychology is the branch of psychology that’s particularly concerned with studying factors that promote happiness and well-being.

Well-being, very simply, means judging life positively and feeling good. One critical distinction that psychologists make is between kinds of well-being.

Hedonic well-being is the type of happiness or contentment that comes from obtaining pleasure and avoiding pain. It’s the kind that you get from eating a marshmallow.

This concept of hedonism dates back to Democritus and Epicurus and was revisited by Hobbes, Bentham, and Mill. The idea is that to be well and feel satisfied with life, a person should experience mental and physical pleasures and enjoyment while avoiding suffering. However, these thinkers also stress that if we want the maximum possible pleasure, we must seek it with rationality and balance, so that pleasures do not dominate us.

In contrast, eudaemonic (which we can also call “altruistic”) well-being is a type of satisfaction derived from spending time doing meaningful activities and having a purpose. Again, the concept of eudaimonia dates back to ancient Greek philosophy when Aristotle proposed it in his work Nicomachean Ethics. For Aristotle, as well as more recent proponents of eudaimonic well-being, one becomes happy by striving to meet their best self and expressing virtue.

Eudaimonic well-being emerges from performing tasks and works that are consistent with your values. It involves pursuing intrinsic goals, living autonomously, being mindful, being benevolent, and being altruistic.

Benefits of the 2 Types of Well-Being

Researchers have sought to see which kind of well-being creates more happiness.

What they found was that each actually creates different outcomes—and one isn’t necessarily better than the other.

For example, some research finds that hedonic behaviors increase positive emotions, and life satisfaction, can help regulate emotions, and reduce negative emotions like stress and depression.

On the other hand, eudaimonic behaviors tend to create greater meaning in life and experiences of elevation—positive feelings from witnessing moral virtue. It tends to create feelings of overall life satisfaction.

So which is better? While some psychologists argue for one over the other, most people argue that both are needed to truly flourish.

Hedonic Adaptation and a Happiness Setpoint

While both may be necessary, there may be a limitation of hedonic pleasures—they don’t last.

Hedonic adaptation is a theory that postulates that people have an initial level of happiness and they eventually return to that point after both bad or painful experiences and good or pleasurable ones.

This may explain why the effect of pleasurable events is relatively short-lived on our well-being. While we may enjoy a spike of pleasure from attending a party, eating delicious food, or going for a run, we eventually return to our baseline.

During this psychological process, our body will produce a substance—dopamine.

However, eudaimonic activities may be more effective at creating life satisfaction over time.

Eudaimonic Well-Being and Health

Eudaimonic well-being focuses on the realization of your potential and pursuing meaningful activities. It emphasizes autonomy, personal growth, positive relationships with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance.

This doesn’t just leave you feeling happy, but it also seems to contribute meaningfully to physical health.

In one community-based epidemiology study, researchers looked at longitudinal data from 1,238 older adults. They found that individuals who reported greater purpose in life at baseline testing—i.e. those who had higher scores on the “purpose in life” scale—were less likely to have died five years later. In other words, the purpose-in-life scores of the people that died (3.5 out of 5) were statistically significantly lower than the scores of those that survived (3.7 out of 5).

In another study, researchers looked at longitudinal data from 900 older adults that lived in the community. They wanted to know if having a purpose in life was related to better mental health. After a seven-year follow-up, the researchers found that individuals that reported having a greater sense of purpose in their lives were much less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. A person in the 90th percentile on the purpose in life scale was found to be 2.4 times more likely to remain free of Alzheimer’s disease.

Other studies have expanded these findings to other facets of physical health. One meta-analysis found that people with a sense of purpose are less likely to have a stroke or heart disease—they found a pooled relative risk of 0.83. People with a sense of purpose are also more likely to engage in behaviors that contribute to sustained health, like doing cancer screenings or getting tests for high cholesterol.

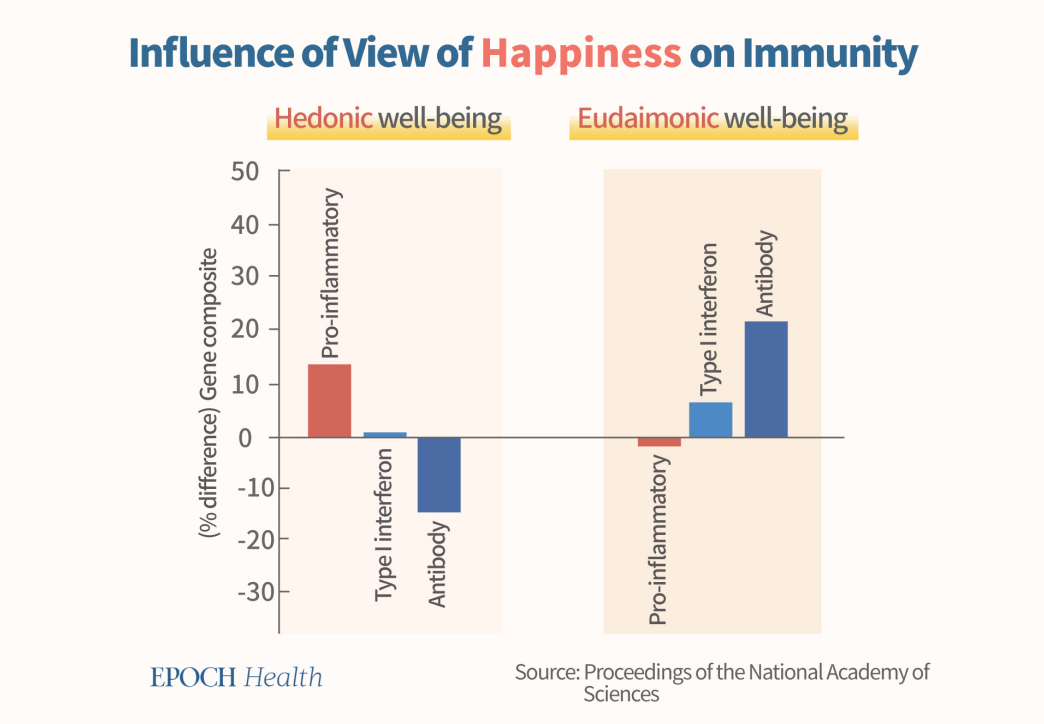

In a 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the immune system indicators of people with two different views of well-being were examined. One view was eudaimonic well-being, which is inclined to pursue human justice and noble goals, and hedonic well-being, which is more inclined to pursue personal sensory enjoyment. It was discovered that people who pursued eudaimonic well-being had higher interferon gene expression, higher ability to produce antibodies, and significantly lower expression of inflammatory genes.

The overall effect of their gene expression is more favorable for their body to fight against viruses, including SARS-CoV-2.

Together, these studies suggest that feeling connected to a purpose not only brings a kind of psychological well-being but also has very clear benefits for physical health, too.

Hedonic Happiness and Health

Because it is a philosophy that encourages the continuous search for pleasure, hedonistic behavior can create health problems and other harmful consequences if not moderated.

For example, eating sugary foods, smoking, and using psychoactive drugs can be problematic for long-term health and life satisfaction even if they provide some immediate pleasures. That seems to be one argument against a purely hedonic vision of well-being.

This is where the marshmallow study helps us understand the link between hedonistic behaviors and well-being.

Psychological proponents of hedonism note that many people—most people, in fact—successfully refrain from over-indulging in hedonistic activities most of the time. They point out in research on self-control that people are able to delay gratification to experience greater pleasure later.

Most of us don’t over-indulge in sugary foods because we know it will make us feel ill later and will make us unhealthy. So we give up pleasure now to avoid pain later. Similarly, they would argue that most people don’t smoke because they know that it will cause them suffering later.

So proponents of hedonic well-being aren’t necessarily saying that the pursuit of pleasures now will create well-being. They would argue that some short-term pleasures should potentially be avoided in order to promote longer-term pleasures—and avoid unpleasant chronic illness—down the road.

Both Are Important—and Both Can be Taken to Excess

Rather than one of these views of well-being being “right” it’s likely that both are important for us.

For example, some research suggests that people who seek both tend to report having higher levels of well-being than people who pursue only one. They also tend to have better mental health than either one of the groups on their own.

Not only that, but the well-being they achieve may be more well-rounded. In other words, the two different types of well-being may fill different gaps. Hedonia seems to affect people more in a temporary way in the present, whereas Eudonomia seems to work in a longer-term way.

Just as both are necessary, both can be taken to excess.

We’ve already mentioned the dangers of excessive hedonism. When taken too far, it can lead to impulsivity, addiction, greed, and escapism. It can also create selfishness and antisocial behavior.

But eudaimonism, too, can be taken to excess. When pursued too far, this can look like a workaholic lifestyle, exhaustion, and excessive self-sacrifice. It can mean burnout, losing touch with one’s body, overthinking things, and becoming paralyzed by worry and stress.

Both are necessary, and both must be balanced to result in a healthy life.

How Do You Achieve Well-Being?

So both are important, and so is a balance. How do you achieve that balance and work to optimize your well-being?

First, make sure you’re including eudaimonic actions in your life. The North American lifestyle tends to emphasize the importance of our entertainment and pleasure—we often fall more on the hedonistic side than the eudaimonic side.

So make sure you’re providing that side with the fertile space it needs to grow. That could include:

- Identifying the things that give you purpose and spending time doing those things, including a set of long-term goals

- Pursuing hobbies and interests that help you find meaning

- Engage in deliberate practice to develop your skills

- Volunteering and helping those around you

- Build nurturing relationships with those around you

- Engage in activities to increase self-understanding, like finding your strengths or clarifying your values

If you find yourself overworked, exhausted, or overwhelmed by strong negative emotions, you may need to focus more on the hedonistic side. Take some time to stop and smell the roses or engage in pleasurable activities. But try to avoid activities that provide only short-term pleasure but that will create more suffering in the longer term.

Here are some examples:

- Spend time having a delicious meal with close friends or family

- Take time to do an activity you take pleasure in, such as reading a good book, going for a walk, or gardening

- Visit a fresh food or flower market

- Engage in activities that will provide long-term pleasure and health benefits, such as mindfulness meditation, enjoying nature, or playing sports

- Enjoy a game with friends

Of course, the precise activities to do depend on the individual person—your individual values, desires, and pleasures. Each person’s idea of “the good life” differs, and so each person may live their best life differently from others.

But for all of us, it appears that we can arrive at well-being through a combination of enjoying life’s pleasures while also seeking meaning and purpose.

Neither one, on its own, appears to provide as much benefit as both do together. And both may become excessive if you’re not careful.

Instead, we should seek balance.

References

Anic, P., & Tončić, M. (2013). Orientations to happiness, subjective well-being, and life goals. Psihologijske teme, 22(1), 135-153.

Aristotle (350 B.C.E.) Nicomachean Ethics

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & King, L. A. (2009). Two traditions of happiness research, not two distinct types of happiness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 208-211.

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(5), 574.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Well-being Concepts.

Crimmins, J. E. (2021). Jeremy Bentham. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Diano, C. (2022). Epicurus: Greek Philosopher. Britannica

Duignan, B. (2022). Democritus: Greek Philosopher. Britannica

Fredrickson, B. L., Grewen, K. M., Coffey, K. A., Algoe, S. B., Firestine, A. M., Arevalo, J. M., … & Cole, S. W. (2013). A functional genomic perspective on human well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(33), 13684-13689.

Goodreads (n.d.). Abraham Joshua Heschel > Quotes > Quotable Quote.

Henderson, L. W., Knight, T., & Richardson, B. (2013). An exploration of the well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic behavior. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(4), 322-336.

Huta, V. (2016). An overview of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being concepts. The Routledge Handbook of Media Use and Well-being, 14-33.

Igniter Media (2009, September 24). The Marshmallow Test | Igniter Media | Church Video [YouTube Video].

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation.

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207-222.

Kim, E. S., Strecher, V. J., & Ryff, C. D. (2014). Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(46), 16331-16336.

Macleod, C. (2020). John Stuart Mill. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Mischel, W., & Ebbesen, E. B. (1970). Attention in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16(2), 329–337.

Mount Sinai Medical Center (2015). Have a sense of purpose in life? It may protect your heart. Science Daily.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potential: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141-166.

Ryan, R. M., & Martela, F. (2016). Eudaimonia as a way of living: Connecting Aristotle with self-determination theory. In Handbook of eudaimonic well-being (pp. 109-122). Springer, Cham.

Sorrel, T. (2022). Thomas Hobbes: English Philosopher. Britannica

Stanford University. (n.d.). Heschel, Abraham Joshua: Biography.

Williams, D. M., Rhodes, R. E., & Conner, M. T. (2018). Psychological hedonism, hedonic motivation, and health behavior. In Affective determinants of health behavior (pp. 204-234).