Mark Twain Comes Back to Life

Distressed Patriotic Flag Unisex T-Shirt - Celebrate Comfort and Country $11.29 USD Get it here>>

To read a play rather than watch it performed is a bit like eating a beef burrito without the accoutrements of salsa, guacamole, or onions. You get the meat of the thing, but it lacks all flair.

The test of this recipe is simple. Have your teenagers read Shakespeare’s “Henry V.” Next, have them watch Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 film adaptation of the same play. Then pack some diced onions into those food missiles, slather on the guacamole, douse them in salsa, and serve them up when your kids ask for a second run on Branagh’s movie.

Plays—tragedy, comedy, farce, and all the rest—aren’t novels, written as a dialogue by the author, the reader, and the imagination. Plays are collaborative works aimed at the stage. The director, the actors, the costume and makeup crews, the sets: These are the people and things that breathe life, color, and magic into a playwright’s script. Shakespeare’s soliloquies, speeches, and dialogues are the work of a genius, yes, but he wrote them to be performed in front of a live audience.

It was just such an audience—men and women seated in a theater, entranced by the performance of the actors on a stage—that one of America’s greatest writers hoped to reach. And time and again he failed to achieve that ambition.

Love and Despair

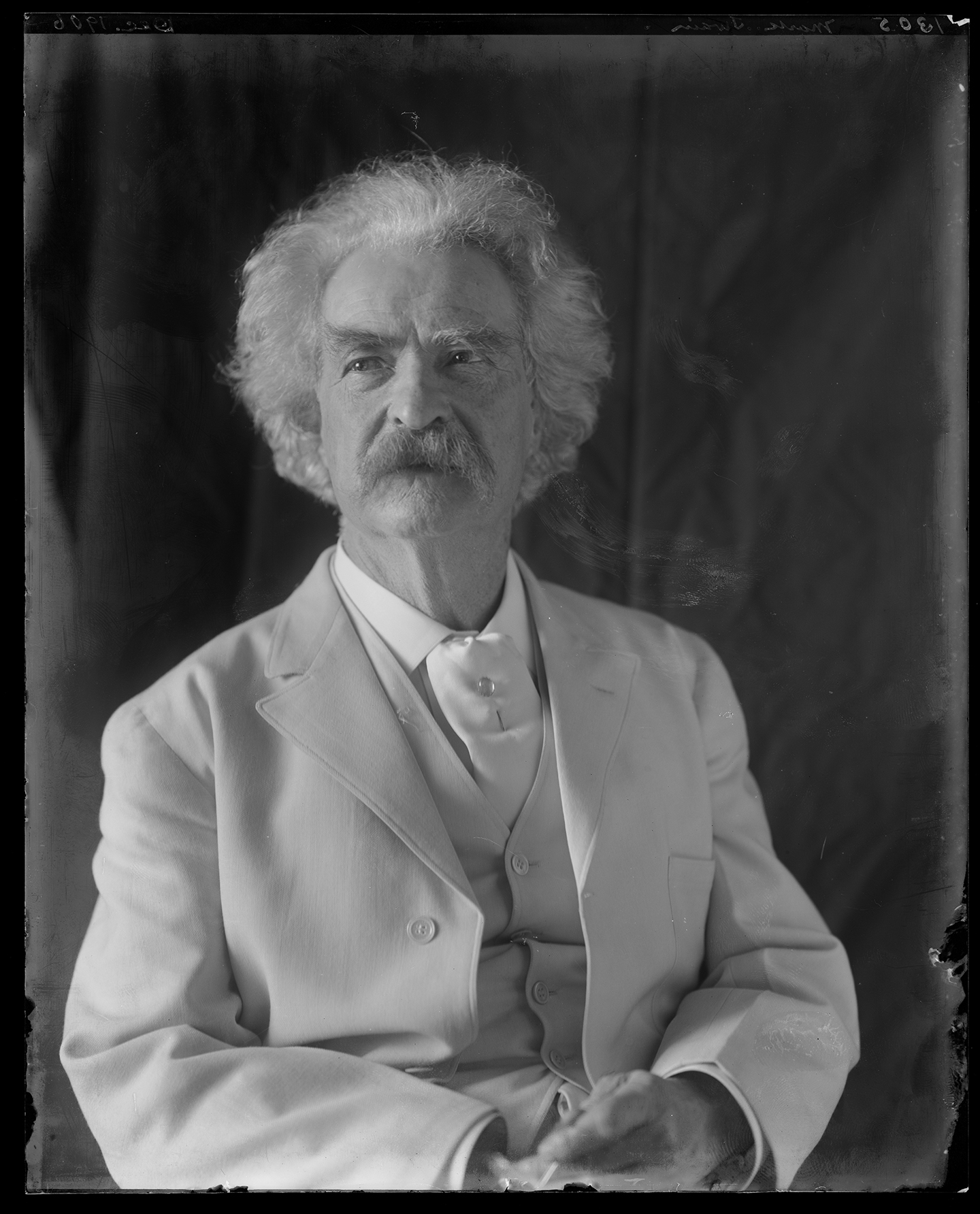

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835–1910), better known as Mark Twain, loved the theater from boyhood, when he attended the minstrel shows that visited his hometown of Hannibal, Missouri. As an adult, he attended plays whenever possible and at times wrote reviews of them for various papers. He enthusiastically participated in amateur theatricals, and after acquiring fame for books like “Life on the Mississippi” and “Huckleberry Finn,” he became enormously popular for his dramatic and often hilarious monologues and readings.

Yet the man revered by critics and readers as the father of American literature gained no traction as a playwright. Despite repeated attempts, this master of fiction and the essay couldn’t ignite the footlights of the stage. One play, “Colonel Sellers,” did prove financially lucrative, but Twain was never happy with the production and seemed to agree with his critics that it was “a wretched thing.”

And then, in the winter of 1898, Twain wrote a comedy that he was convinced could be “produced simultaneously in London and New York.”

Another Shot at the Stage

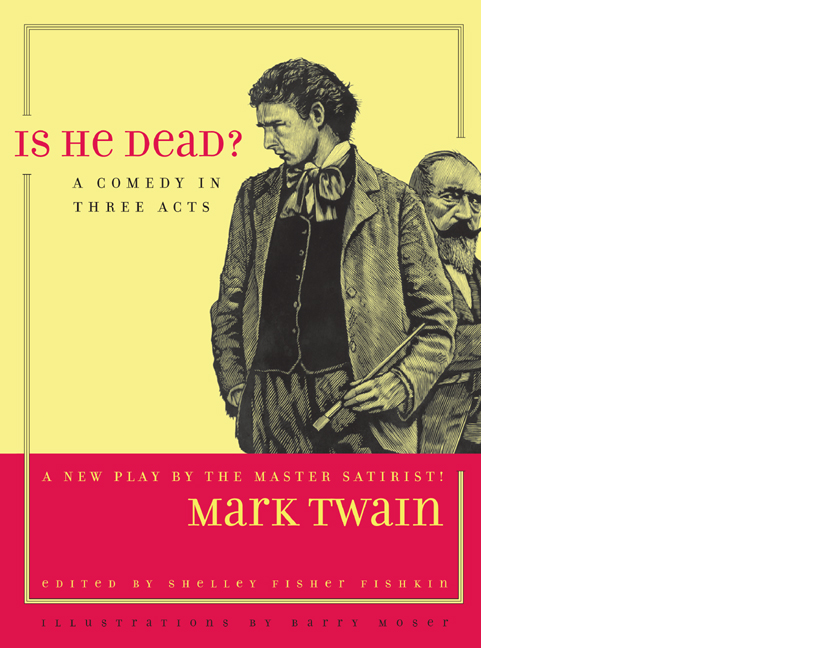

“Is He Dead? A Comedy in Three Acts” is the name Twain gave to this work of farce and satire. In her 2003 book by the same title, Twain scholar Shelley Fisher Fishkin brings us both the script of the play as well as valuable commentary and notes. In her “Foreword,” she writes of Twain and his family living in 1898 in Vienna, where he wrote “Is He Dead?” Broke after some unwise investments and still grieving the death of his 24-year-old daughter Susy in 1896, Twain spent a dreary autumn in this city before beginning “Is He Dead?,” the writing of which he described as putting him into “immense spirits as soon as my day has started.”

If we read just the play, as I did, before we tackle Fishkin’s long “Afterword,” where she examines the play in the context of the 1890s, the possible reasons it was never produced, and its suitability for our own time, we are likely to finish the script unimpressed. In brief, the storyline involves a group of artists and others who are in debt to Bastien André, a “picture-dealer and usurer.” When André threatens to ruin them all for their failure to pay him, Agamemnon Buckner, a young artist who goes by the nickname “Chicago,” hatches a scheme to save his friends. He convinces artist and teacher Jean-François Millet, a character very loosely based on the real-life painter of such works as “The Angelus,” to fake his own death, at which point the prices of his paintings skyrocket. André is foiled in all his schemes, and Millet’s name becomes a household word across France.

In Print: Negatives and Positives

For many who read this print version, the play will likely seem unremarkable, creaky, and stilted even for its own time. Twain employs centuries-old dramatic devices to carry the action: a feigned death, a heartless villain out only for money, a young woman torn between true love or saving her family from poverty by marrying that villain, Millet’s cross-dressing as he pretends to be his own non-existent twin sister. There is humor in the dialogue, but as read on the page this will at best bring an occasional chuckle. Finally, Twain populates the stage with so many characters that keeping track of them, especially in the first half of the play, sent me time and again to his “Persons Represented” list.

In his online review at TwainWeb.net, which I read after finishing the script, Mark Dawidziak offers similar negative criticisms. Yet he also points out the value of this piece of writing, which through Fishkin’s efforts is now available to the public for the first time. “Is He Dead?” is, after all, by an American master, and contains examples of Twain’s trademark humor and style. “For better or worse,” Dawidziak writes, “this is a complete work by Mark Twain, folks, and those don’t pull into town on the noon stage every day.”

“The play’s the thing,” said Hamlet, and in the case of “Is He Dead?” those words ring true.

As I noted earlier, words that seem lackluster or clunky in a script can come to life on the stage, given a good director and vibrant actors. In the winter of 2007, nearly five years after Fishkin’s book appeared, “Is He Dead?” finally found the audience dreamed of by the author more than a century ago: “Is He Dead?” appeared on Broadway.

In his New York Times review of the play, “It’s Not Life on the Mississippi, Jean-François Honey,” Ben Brantley first describes Twain’s play as “a silly, formulaic farce, written in 1898, about a starving French painter forced to don women’s clothes.”

Then he immediately adds, “But with the right doctors, even a long-buried dinosaur can be made to dance.” In the case of this dinosaur, these “resurrection artists,” as Brantley calls them, include “the director Michael Blakemore, the playwright David Ives (who adapted Twain’s script) and an infectiously happy cast, led by the wondrous Norbert Leo Butz, that serves a master class in making a meal out of a profiterole.”

Because of this glittering and enthusiastic talent—Brantley is generous in his praise of nearly all on stage—and the tweaking of Twain’s script, “Jokes you would swear you would never laugh at suddenly seem funny.”

If Mark Twain is ensconced in that heaven in which he so often expressed doubt, he must have had a grand laugh that night as well.

A Summing Up

Even if they’ve never read his books, most Americans can at least vaguely identify Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, and Becky Thatcher. Many also possess some sort of knowledge, however dim or muddled, of the plots of the books in which these characters appear. We can safely assume, however, that the same will never be said of “Is He Dead?”

Yet the play will retain a place, however minor, in our literature. Scholars will cherish it, especially as so many scenes and devices hark back to earlier pieces by Twain. They might remember, too, that composing this work breathed new life into Twain’s moribund writing. In the years remaining before his death, he wrote more short stories and essays, and delivered memorable, witty speeches on numerous occasions.

Finally, this play paints a different picture of Twain in his old age than the one commonly accepted—a cynic who had become disillusioned with mankind. As representative of this viewpoint, which Twain’s later writings do indeed reinforce, Fishkin cites Bernard DeVoto, who commented that the older Twain’s dark views depicted “man’s complete helplessness in the grip of the inexorable forces of the universe, and man’s essential cowardice, pettiness and evil.”

And yet, as Fishkin rightly observes, the artists portrayed in “Is He Dead?” are “resourceful, boldly inventive, generous, and good.” The play and its characters give us “a world in which imagination, chutzpah, and collective action trump malevolence and abusive power.”

Somewhere in the man from Hannibal there burned, however faintly, a flicker of faith in humanity.