William Henry Pickering: The Remarkable Sky Explorer

In this installment of ‘Profiles in History,’ we meet a brilliant Bostonian astronomer who gave people a close view of the solar system.

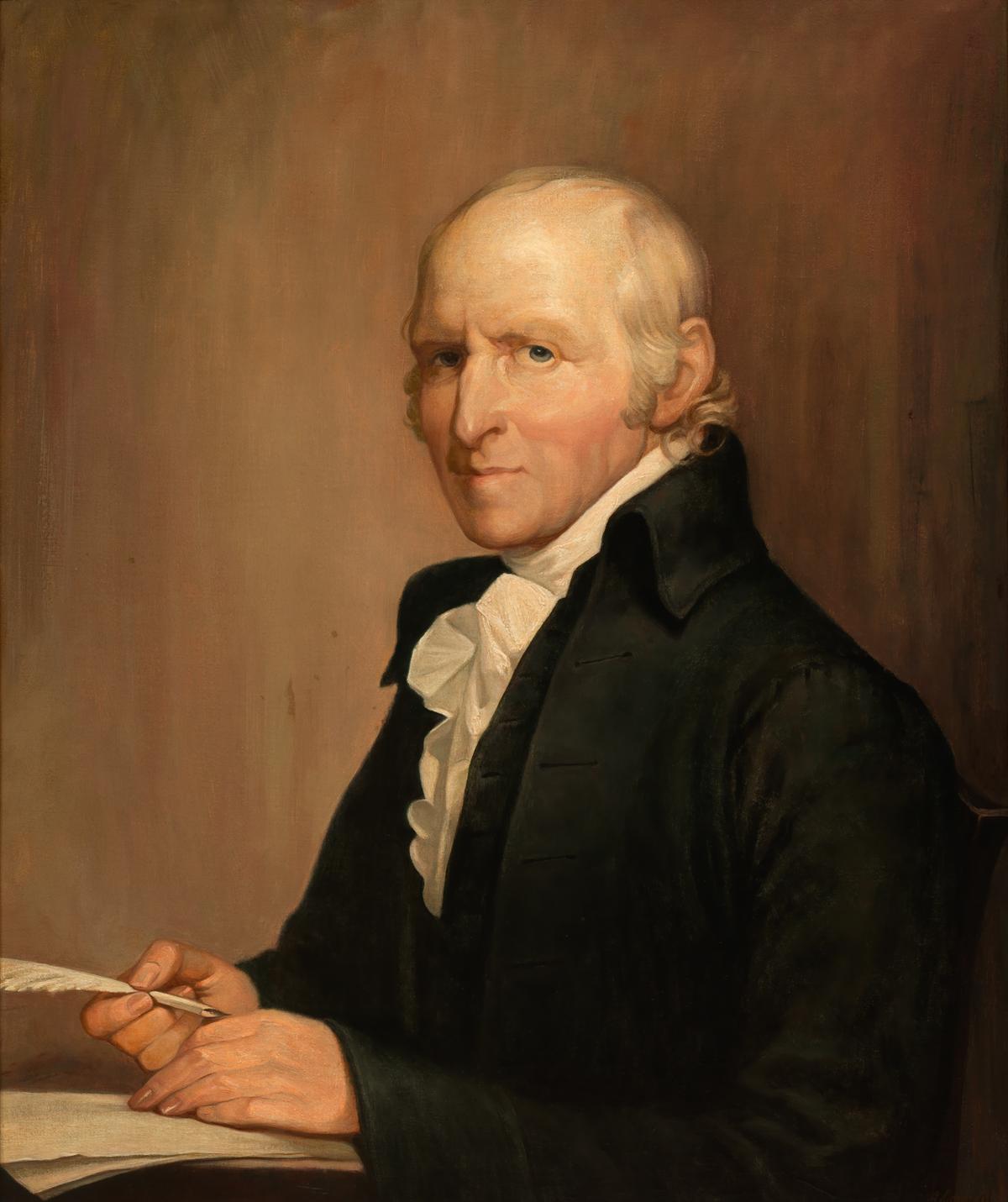

William Henry Pickering (1858–1938) was born in Boston to a prominent American family, one whose roots went back to 1636. Arguably, the most prominent member in the Pickering lineage was his great-grandfather, Timothy Pickering (1745–1829), who had been a colonel, adjutant general, quartermaster general, and a member of the Board of War during the American Revolution. He served as a delegate during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. In the new republic, he was a representative, senator, postmaster general, secretary of war, and secretary of state. The fame of his descendant William Henry Pickering would not be among American politicians, but rather among the stars—literally.

A portrait of Timothy Pickering as secretary of state, before 1828, by Gilbert Stuart. Public Domain

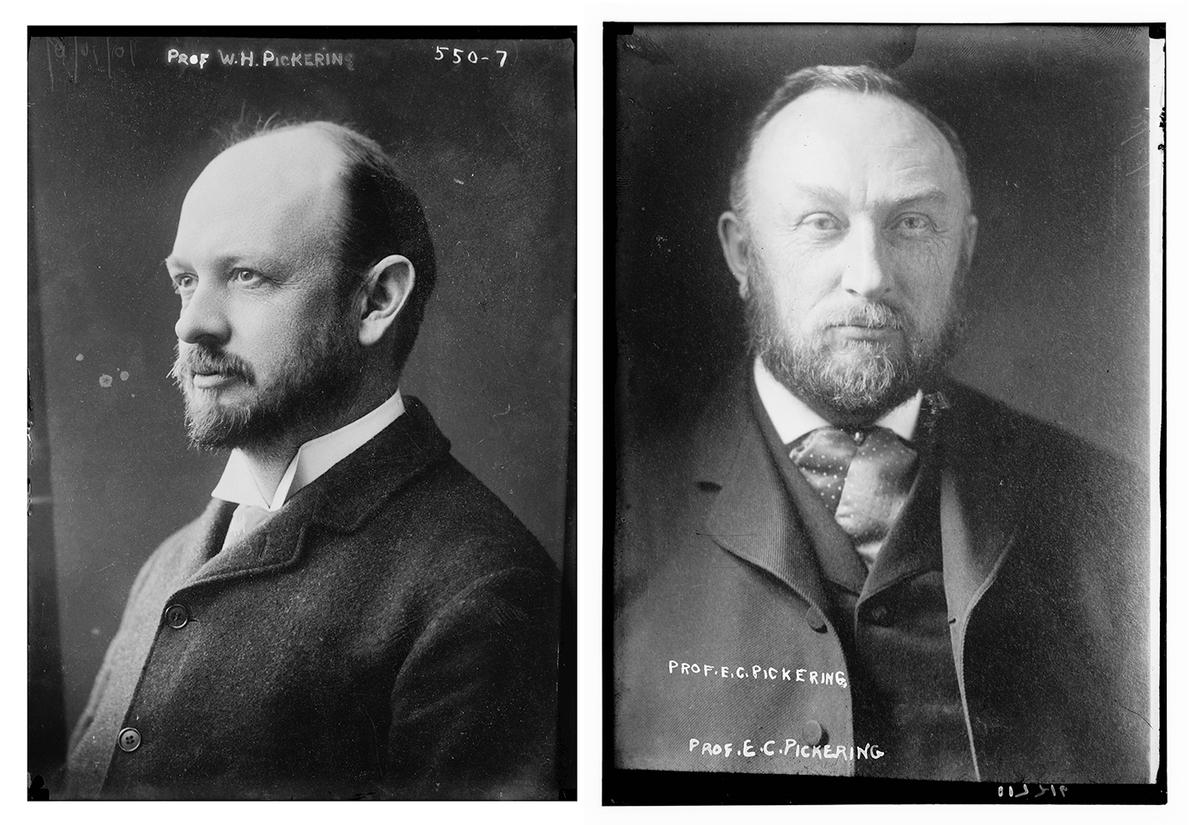

By the time Pickering began attending Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), his older brother Edward (1856–1919) had been a physics professor at the school for a decade. Shortly after Pickering’s arrival at MIT, Edward was appointed professor of astronomy at Harvard College. It was the same school Timothy Pickering had graduated from more than a century prior. Edward was also appointed director of the Harvard College Observatory, a position he held for more than 40 years and one that would greatly benefit his younger brother.

William Henry Pickering graduated from MIT in 1879 and was hired there as a physics professor the following year. He remained in that position until 1887 when he was hired as an assistant professor of astronomy at Harvard and was brought on staff at the Harvard College Observatory.

Astronomer brothers (L) William Henry Pickering, 1909, and Edward Charles Pickering. Library of Congress. Public Domain

During these teaching years, possibly as early as 1882, Pickering began to take celestial photography using dry plates. As he became more proficient in dry plate photography, his photos would have profound effects on the astronomical community.

Searching California

During Pickering’s final year teaching at MIT, the Harvard Observatory received a large donation from the Boyden Fund with the intention to build a new observation station. Pickering seemed to be just the person to find a new locale for it.

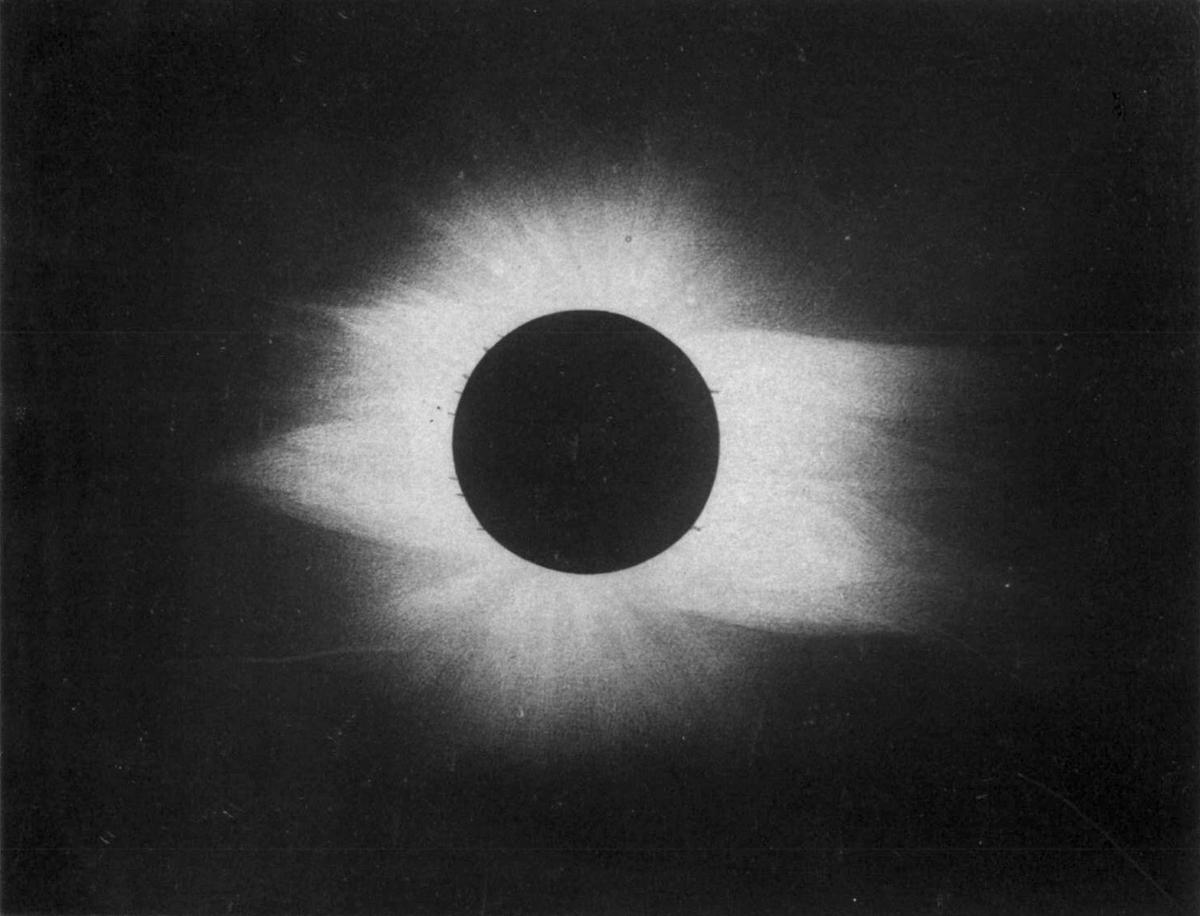

At the end of 1888, Pickering led a scientific expedition to California in order to observe the solar eclipse, which was to take place on New Year’s Day 1889. During this expedition, Pickering and his elder brother, Edward, who had remained at Harvard, collaborated with the New York Herald to relay information about the team’s findings.

Photograph of the Jan. 1, 1889 solar eclipse from Norman, Calif. Public Domain

While on the lookout for an observation point, Pickering and his team, which included optician Alvan Clark, visited Mount Wilson, one of the peaks in the San Gabriel Mountains. He proposed Mount Wilson to Harvard as the place for “the largest and finest telescope in the world.”

With this proposed location for the Boyden Station, Harvard College Observatory hoped to compete with the University of California’s recently opened Lick Observatory, located on Mount Hamilton along Diablo Range. The construction of the station, however, met with setbacks and hardships, specifically during the winter of 1889–90. After about 18 months, they abandoned the location. Mount Wilson Observatory was later built on this site.

How About Peru?

The year of that harsh winter in 1889, Edward sent Solon Bailey to South America to find a location for the Boyden Station. After two years, Bailey chose Aréquipa in southern Peru. The city resides at an elevation of more than 7,000 feet, surrounded by three volcanoes. Edward chose Pickering to oversee the construction of the Boyden Station, and then remain there as its director.

Although Edward wanted the station to relay spectrographic and photometric data to Harvard, Pickering was interested in studying Mars during its opposition—an event that takes place approximately every 26 months. In 1892, Pickering reestablished communication with the New York Herald, relaying his observations. Throughout the year, sans a gap between July 9 and Sept. 24, Pickering studied Mars every night, creating 373 drawings of the planet’s various features. But this wasn’t the purpose of his appointment. His brother, frustrated with Pickering’s research and lack of communication, recalled him to Massachusetts.

Back to America

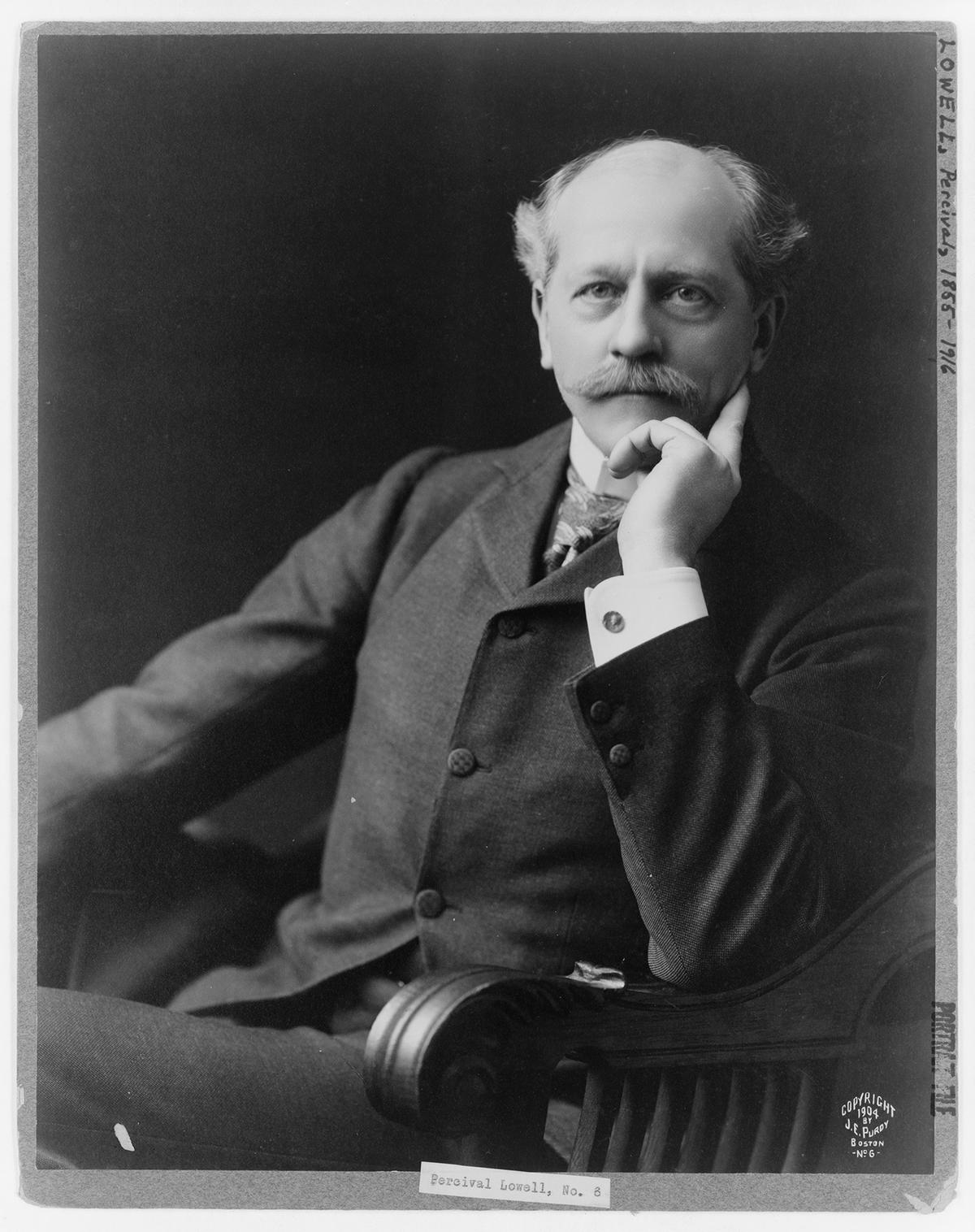

A portrait of astronomer Percival Lowell in 1904. Library of Congress. Public Domain

After Pickering returned, he made the acquaintance of wealthy businessman and amateur astronomer, Percival Lowell. Pickering assisted Lowell in establishing his own observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. Lowell was a Mars enthusiast, who would become famous for claiming to have seen canals on Mars—canals created by an intelligent life form. This claim was soon disproven. More importantly, Lowell theorized the possibility of a ninth planet in the solar system, a theory in which Pickering would play a significant role substantiating.

- Grocery Stores Increase Donations in Response to Democratic Criticism

- UK Healthcare Ranked Last Among Other Wealthy Nations