Boeing assumes control of Spirit manufacturer following in-flight incident | Business Updates

Spirit AeroSystems was a company little-known outside the aviation industry until January this year.

Then, however, the fuselage maker was flung into the spotlight when a Boeing 737 MAX jet operated by Alaska Airlines suffered a mid-air blow-out of a door plug.

Spirit, whose operation in Wichita, Kansas, had made the fuselage for the jet, saw its shares plunge by as much as 20% and found the quality of its work coming under heavy scrutiny as Boeing scrambled to convince regulators and customers that its aircraft were safe.

It subsequently emerged that the fuselage contained defective rivets but a preliminary report by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) also found that four bolts needed to secure the door plug were missing – pointing to errors by Boeing’s own workers at its plant at Renton, Washington.

Money latest:

‘Bleak’ new security measure seen in Tesco

One solution rapidly touted to resolve quality issues at both companies was for Boeing to acquire Spirit – which was originally part of Boeing but was spun off as a separate company in 2005.

The pair began negotiations in March this year and, today, an agreement was reached.

Boeing will pay $4.7bn (£3.7bn) in shares to acquire Spirit. It will also take on Spirit’s debt – putting a total enterprise value on the business of $8.3bn (£6.6bn).

Separately, Spirit will pay Airbus $559m to take on work done for the European aircraft manufacturer at four of its plants. These include the production of A350 fuselage sections in Kinston, North Carolina and at Saint Nazaire on the west coast of France, as well as the production of wings and mid-fuselage for the A220 in Belfast.

The latter, which employs more than 3,000 people, is one of Northern Ireland’s biggest private sector employers and its second biggest manufacturing employer.

The sale to Airbus marks the second time the operation has changed hands in five years. It was acquired by Spirit in 2019 from Canadian engineering combine Bombardier – which had itself bought the business, previously called Short Brothers, in 1989. Shorts, which was founded in 1908, famously claimed to be the world’s first aircraft maker after receiving an order the following year from the aviation pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright. It moved to Belfast in 1936.

The takeover of Spirit has taken a while to stitch together because of the involvement of Airbus which had, reportedly, been seeking compensation of $1bn for taking on the operations – which also include a site at Casablanca in Morocco.

The Airbus transaction – it is being compensated because the operations it is taking on are loss-making – has echoes of a deal that Airbus cut with Bombardier in 2017 to buy the latter’s C-Series small jetliner programme for just $1. The jet was later renamed the A220.

Not included in the sale, though, are Spirit’s other operations in Belfast which do work for customers other than Airbus and operations in Prestwick, South Ayrshire, that do support Airbus programmes. Spirit said today that it was seeking to sell these two businesses and a third one in Subang, Malaysia.

For Boeing, taking on the activities of its biggest supplier is hugely important in seeking to better integrate fuselage manufacturing into its overall processes, a key element in its aim of overseeing quality control more effectively.

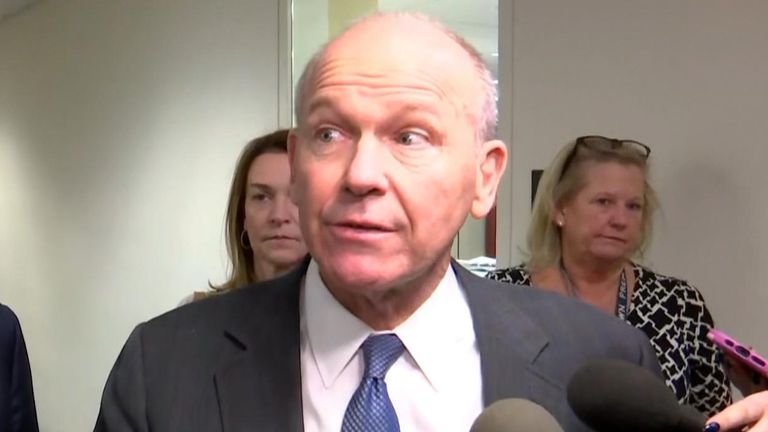

As Dave Calhoun, Boeing’s chief executive, put it: “By reintegrating Spirit, we can fully align our commercial production systems, including our quality and safety management systems, and our workforce with the same priorities, incentives and outcomes, focused on safety and quality.

“We believe this agreement is in the best interest of the flying public, our airline customers, Spirit and Boeing employees, our shareholders and the country as a whole.”

One troubled company absorbs another

No one should be under any illusions, though, that this is one troubled company taking control of another troubled company.

Integrating Spirit and its 14,000 employees into Boeing will take a long time – and, accordingly, it will be some time before the company can convince its stakeholders that it has got to grips with quality issues at both Spirit and in its own operations.

It is also worth noting that the deal, which is not expected to close until the middle of next year, is being done in shares and not cash.

This is in order to protect Boeing’s credit rating as the company, which has debts of nearly $58bn, fights to stave off a downgrade to ‘junk’ status.

Moody’s joined S&P and Fitch in April in downgrading Boeing’s credit rating to ‘Baa3’ (also known as triple-B minus) while all three have Boeing on a so-called ‘negative outlook’ list – which means it could be further downgraded in future. A downgrade to junk status would expose Boeing to the risk of some investors not being allowed to buy its bonds in future.

Brian West, Boeing’s chief financial officer, told investors in April that the company – which burned through $4bn of cash in the first three months of the year – was making a priority of maintaining an investment grade rating.

In the meantime, Bloomberg reported over the weekend that Boeing is to be charged with fraud after violating the terms of a 2021 deferred prosecution agreement with the US Justice Department in May this year. That could expose the company to tens of millions of dollars worth of fines.

So, while this agreement with Spirit is probably a step in the right direction, Boeing still has numerous challenges with which to contend.

More from Sky News:

Strikes called off at Port Talbot steelworks

Energy price cap falls today but ‘£600 lift to bills ahead’

Who could take over as Boeing boss?

Perhaps the biggest question still being asked by investors is when the company will name a new chief executive to replace Mr Calhoun who, at the end of March, announced he would step down before the end of the year.

Stephanie Pope, a long-time Boeing executive who was made chief operating officer earlier this year, is the top internal candidate but Boeing is thought to be keen to hire a new broom from outside the company.

That process, though, has taken time. The Wall Street Journal reported last month that Larry Culp, the chief executive of GE Aerospace, had turned down the role – while others linked with it include

Source link