The Links Between Canada’s Fathers of Confederation and the War of 1812

Commentary

War and memories of war have always been important to Canadians—even the Fathers of Confederation.

In my last two years of high school, I worked Saturdays and summers in West Vancouver’s best second-hand bookshop, the Bookstall in Ambleside, where my boss was a World War II veteran named David Angus Moon. He’d served in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, the RCN(R), and the Royal Navy, and in June 1944, in command or second-in-command of a landing craft in the Battle of Normandy.

He once showed me a photograph of his younger self, whiskers dark instead of white under a well-worn forage cap, with some mates among the ruins of Bernières-sur-Mer at Juno Beach a few weeks after D-Day. It would have been about 1987, more than 40 years after the event, that he showed me the picture, but like yesterday to Dave Moon, who died in 2006. “It’s a war” he would say of the losing battle to keep order among the books.

Today, the last veterans of that war who are still around are getting pretty venerable, like 101-year-old Bryce Chase, who lives in Calgary’s Colonel Belcher retirement home, or Victor Osborne of Nanaimo, who is 106.

Despite the passage of time, we honour them still. People want to remember the great deeds of our forebears and those who died. On Remembrance Day, 35,000 turned out in Ottawa, according to the Royal Canadian Legion, and there were big crowds everywhere—testament that Canadians want to honour their veterans, including the 40,000 who completed tours in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014.

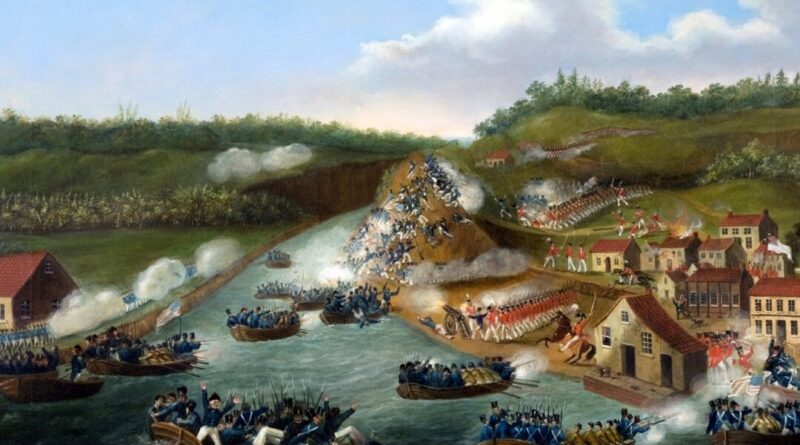

When Canada, already 200 years old, was re-founded as a federal Dominion in 1867, some of the Fathers of Confederation were veterans of the War of 1812 or had a close connection to veterans. The war had ended 50 years before the Charlottetown Conference and was part of fairly recent memory and family lore. A fair number of the Fathers were only one generation removed from the war.

Sir John A. Macdonald. CP Photo/National Archives of Canada

Sir John A. Macdonald’s uncle, Lt.-Col. Donald MacPherson, saw action in U.S. Commodore Isaac Chauncey’s attack on Kingston Harbour during the War of 1812. One of MacPherson’s six daughters (thus Macdonald’s cousins) could remember shots penetrating “the wooden walls of the pretty white cottage that then did duty as the commandant’s residence.” (To imagine Upper Canada in those days, think rustic Jane Austen but with bullets).